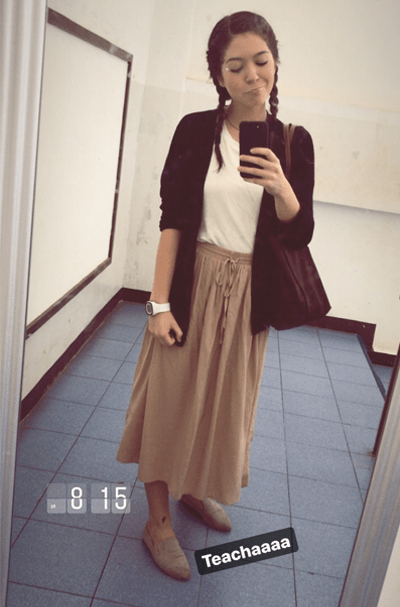

Goodmorning, Teachaa

After talking broadly about the trips I have taken, I thought I would use this post to chronicle a glimpse of what I experience on the day-to-day, specifically each morning at school. Typically, I arrive around 7:50 when the teacher on side gate duty is impatiently holding the gate open for the last students sprinting to make it, and myself. I slide in and wai: “Sawadee ka,” I say in greeting, “Hello! Kap khun ka for holding the gate.” My Thai sucks. It’s usually a mix of Thai and English, with most Thai phrases being repeated quickly in English (sawadee-ka-hello), almost in apology for how attrociaous I sound. She smiles curtly as she locks the gate, dooming all latecomers to the extra block’s walk to the front gate.

I drop off my bag in my office, slip into my school shoes, sign in, and head to the huge, covered, outdoor gathering area where the 3000+ students already stand in neat rows, taking attendance and chattering. I am an advisor for Mathayom 5 (the age equivalent of Juniors in high school), but due to the fact that mai kow jai—I don’t understand—Thai or anything that is going on, I mostly just stand there and look pretty. Occasionally, Cream—the class leader—runs up to me with papers written completely in Thai, hands them to me, and points to lines for me to sign. I dutifully initial, and hand them back to her; nothing bad has come of this strategy yet.

I scan the rows for the M5 teachers I recognize so that I know where to stand today. I’m in my own world and remember —shit—I almost forgot my manners. Wai, wai, wai, as I pass Thai teachers; some wai back; other, older ones, simply nod in my direction. I’m still not confident I completely understand the whole waiing concept. The wai itself is a slight bow with the hands together; it is a greeting, a show of respect. The subordinate initiates the wai with the superior, and the superior (or equal) then returns the wai. Students wai teachers all day long, and that is usually accepted with a nod of acknowledgement from the teacher or, if you’re bridging cultures like me, a smile and a loud “hello.” While the student-teacher power dynamic is pretty straightforward, superiority is not always black and white. For example, in the school setting, elder teachers are definitely superior, as are those who hold a higher position than myself (how would I know what someone’s postition is? Answer: I wouldn’t). But riddle me this: what do you do when faced with someone who is older than you, but in a lower position?

For example, there is a custodian who works in our building; she is not old, but she is definitely older than me. One of the first days, I hit her with a wai and a, “Sawadee ka.” She giggled—ok so maybe I wasn’t supposed to wai her? I thought—but she returned the greeting and seemed pleased, the pressed-lip grin remaining on her face and she returned to sweeping. I guessed that not everyone at the school showed her the same respect because a custodian job is held to be lower than the highly regarded teacher position. Whatever—I’m barely a teacher—I wai her every morning , and she always giggles quietly but wais back, appearing to secretly enjoy it.

Anyways, I don’t make it through the morning without waiing at least 30 people. Once I spot where M5 has decided to line up that day, I stand nearby and observe, as some Thai teacher barks loudly on the microphone. I never have any idea what he’s saying, but it never sounds very positive—until occasionally the whole place bursts into laughter, and then I’m confused. When it is time for the flag ceremony to begin, the barking on the microphone stops abruptly and the students stand at attention, facing the flag. The national anthem is sung, the voices of 3,500 students and teachers harmonizing, accompanied by the band. When it is over, everyone turns in unison 90 degrees to the left—we are now facing the Spirit House and Buddhist alter and it is time for prayer. After prayer, everyone turns again, another 90 degrees to the left, facing an image of the King. The song of the royal family plays, some words are said, and then there is a rustle of noise as the men bow and the women curtsey.

More than likely, at some point during this ceremony my co-teacher, another M5 advisor— Rassarin—has snuck up beside me. She stands about a head shorter than I and, in her limited English, speaks to me fondly in a tone one might use on their 2-year-old; she affectionately addresses me as baby. When the ceremony ends, we engage in some only moderately uncomfortable routine small talk, Rassarin never abandoning her sugary tone. We comment on the weather and discuss our weekends—“What did you do this weekend?” I ask on Mondays. “Oh, I sleep!” or “What are you doing this weekend?” I ask on Fridays. “Oh, I sleep!”—and ending with, “Nice day, baby!” when she decides that the pleasantries are over and bids me adieu, marching into the throng of students to fulfill what I assume are the duties of 2 advisors by herself.

And then I slip away, retreating back to the safety of the EP building to settle into my office and wait for first period to start. Depending on the number and sorts of activities taking place where the students remain at the assembly, first period might start on time at 8:20; it might start late, around 8:40; students might roll in from assembly at 9:05, 5 minutes before the period ends. Today only two students showed up to first period, with 15 minutes left until the bell; I found out during second period that all afternoon classes would be cancelled. When these things happen—and they happen often—there is no point in getting frustrated—I guess I’ll push today’s lessons to tomorrow.

Related Posts

Rewriting My Top 10 Reasons: What a Year in Thailand Taught Me

Revisiting my First Blog Post If you scroll through my blog posts, you will find my first post: Why to Teach English in Thailand: My Top 10 Reasons. For anyone... keep reading

Exploring Thailand's Neighbors: Traveling To Laos and Cambodia

When I moved to Thailand, I knew that exploring Southeast Asia was high on my list of things to do. There were many places in Thailand I wanted to see... keep reading

Your Guide to Thailand’s Regions: Picking Your Top Three

My arrival in Thailand was my first experience coming to Asia. Even though I knew I wanted to go to Thailand, I honestly knew very little about its culture. All... keep reading